How Resilient Are Our Agri-Food Value Chains Against The Next Global Crisis? Experts Weigh In

If you had trouble during the pandemic getting the things you wanted to buy, you were far from alone. From the fields to the markets, Covid-19 completely changed how we interact with not only each other, but also with our food. In an increasingly connected global economy, countries will need to take lessons from Covid-19 to apply for the future.

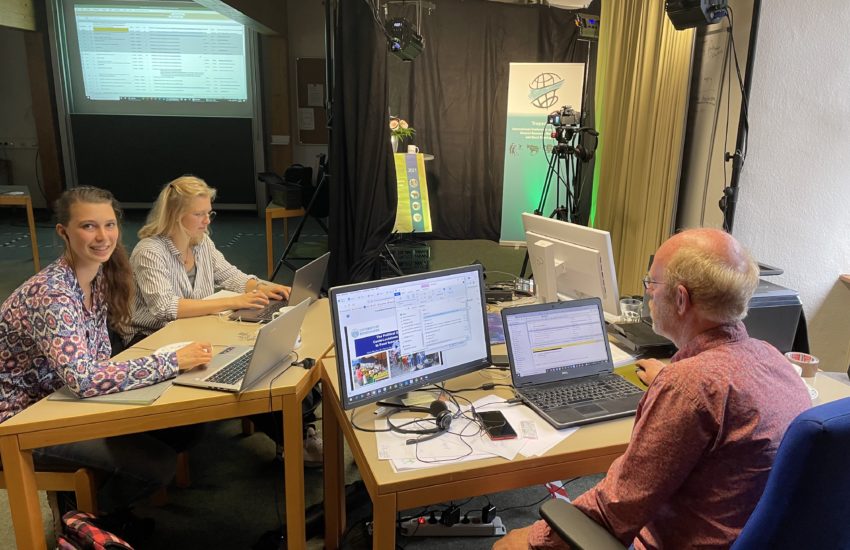

Are you curious about how Covid-19 effected your local market’s ability to stock your favorite items? For an in-depth look, the Tropentag student reporter team approached Dietmar Stoian, World Agroforestry’s lead scientist on value chains, private sector engagement, and investments. Stoian presented his poster “Disruptions and Resilience of Agri-Food Value Chains in Light of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Review of Evidence and Implications for Future Responses” for the Socio-Economics thematic group under “Crises-Poverty-Perseverance” on Day 1 of the Tropentag conference.

One of the roles of the Tropentag student reporters is to bring scientific topics to a general audience. How would you describe your research to the average person who is curious about the role of the Covid-19 pandemic on their local supermarket?

Our literature review looked into more than 100 studies carried out worldwide that examined the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on food production, processing and marketing. Effects on the availability and prices of food varied from country to country, and from market to market. So-called wet markets, that is markets where fresh fruits and vegetables are traded, continued to be among the most relevant market outlets for many consumers, though several of them were affected by full or partial closure at the peak of the pandemic. Supermarkets were generally less affected as they faced less difficulties to comply with safety and hygiene measures, and they also benefited from better organization of their supply chains. In some countries, there was a notable increase of e-commerce (online food orders) which may have lasting effects in given cases.

Did your research uncover any one pandemic-related policy change as the main bottleneck for global agri-food production and transportation?

Policy response to the pandemic varied widely, from more or less strict lockdown measures to support to farmers (e.g. facilitation of access to farming inputs), food processors (e.g. tax breaks, longer periods for loan repayment) and resource-poor consumers (e.g. food coupons). In some cases, restrictions in the movement of goods and people were so rigid that fresh produce could not be transported in time to food processors or to the market. As a result, food losses and waste increased and farmers, processors and traders faced income shortfalls. Most of these effects were ephemeral though, typically not exceeding more than a few weeks.

Related to the questions above, would you agree that the gap between developed and developing nations’ abilities to respond to pandemics and global crises became clearer during the Covid-19 pandemic? If so, in what ways did the effects on the agri-food systems differ between developed and developing nations?

Response capacities in the Global North were indeed different from those in the Global South. Industrialized countries took advantage of their greater capacity to become indebted, allowing them to support the different actors along agri-food value chains in varied ways. Governments in the Global North could also mobilize the resources needed to purchase significant amounts of vaccine to protect their most vulnerable populations and, over time, broader sections of their societies. Still, several governments in the Global South deserve recognition for promoting preventive measures early on in the pandemic and maintaining food production, processing and marketing to the extent possible, despite their budgetary and fiduciary constraints.

Going forward, what kind of precautions does your team recommend to prevent the next global crisis from crippling agri-food value chains?

Preventing similar crises in the future may be difficult given the intrinsic nature of such pandemics, though effective early warning systems and rapid response to new or known pathogens with the potential to develop into a pandemic can go a long way. What can and needs to be strengthened is the preparedness for such crises, for example by increasing the capacity to store staple foods at national, community and household levels, becoming less dependent on imports of critical foods, and developing monitoring capacity that allows to limit restrictions in the movement of goods and people to those areas where an outbreak exceeds given thresholds. Emergency relief capacity can also be strengthened by a clear focus on the most vulnerable populations and effective ways to reach to them. This involves, among other, investments in basic infrastructure, the establishment of community-level safety nets, and local rapid response squads that can be mobilized during a crisis.

What does Tropentag mean for you?

It’s a great opportunity to meet with a significant number of other researchers working on diverse topics in relation to agricultural and rural development in tropical countries, from early career to more seasoned scientists (like myself). I particularly like the involvement of students as engaged reporters – an idea first realized during the Tropentag in Vienna (2017). This is a great way for them to make contacts and to become familiar with a broad array of relevant topics. Well done – and best wishes for a successful Tropentag 2021.