Shifting Which Paradigms exactly?

The mood in the lecture hall B1 was a little solemn as Professor Folkard Asch handed over the mic to Dr. Chagunda for his welcome speech, officially marking the beginning of proceedings. We didn’t know what to expect, but the tone was about to be set for the next few days. Almost immediately, we were confronted with some issues at hand. The event host, Prof Chagunda goes straight to the point in true administrator style; Despite the great strides in agricultural productivity, chronic malnutrition remains a problem in many parts of the world. He reminds us that food security is not a production issue, rather a distribution issue. How is it – he asks – that smallholders, people who produce 70% of food in the world are the most vulnerable to hunger and malnutrition? This and the fact that agriculture accounts for 70% of global water pollution are 2 reasons why Prof. Chagunda insists that several paradigm shifts are needed. Since agriculture contributes to good human, animal & environmental health, these challenges should be addressed in a multidisciplinary nature which, thankfully, is what Tropentag seeks to do. Younger scientists, of course, aren’t excluded from the discourse – They are the future, the future is today. The audience is left inspired.

In a previous interview, Prof. Chagunda elaborates on the topic of shifting paradigms in his own research. Click here for the full interview:

Unlearning: “Food is From the Supermarket”

Dr. Jimmy Smith of International Livestock Research Institute, is soon invited to take the stage. Albeit from a projector screen, he manages to warm the room with a personal story about his childhood in Guyana, where he recalls constant reminders from his father of food scarcity and the welfare of the rural farmers who grew their food. Compared to today’s culture where, he says, the belief that food comes from the supermarket is a 21st century problem. By the time earth’s population stabilises in 2100, says Dr. Smith, we will need 60% more food to feed ourselves. That food will be produced from a fixed land base which is reaching its ecological limits, and also facing climate change. The challenge is not only producing enough food, but also ensuring that we are well nourished, in sustainable ways, especially for African & Asian populations which will grow quickest.

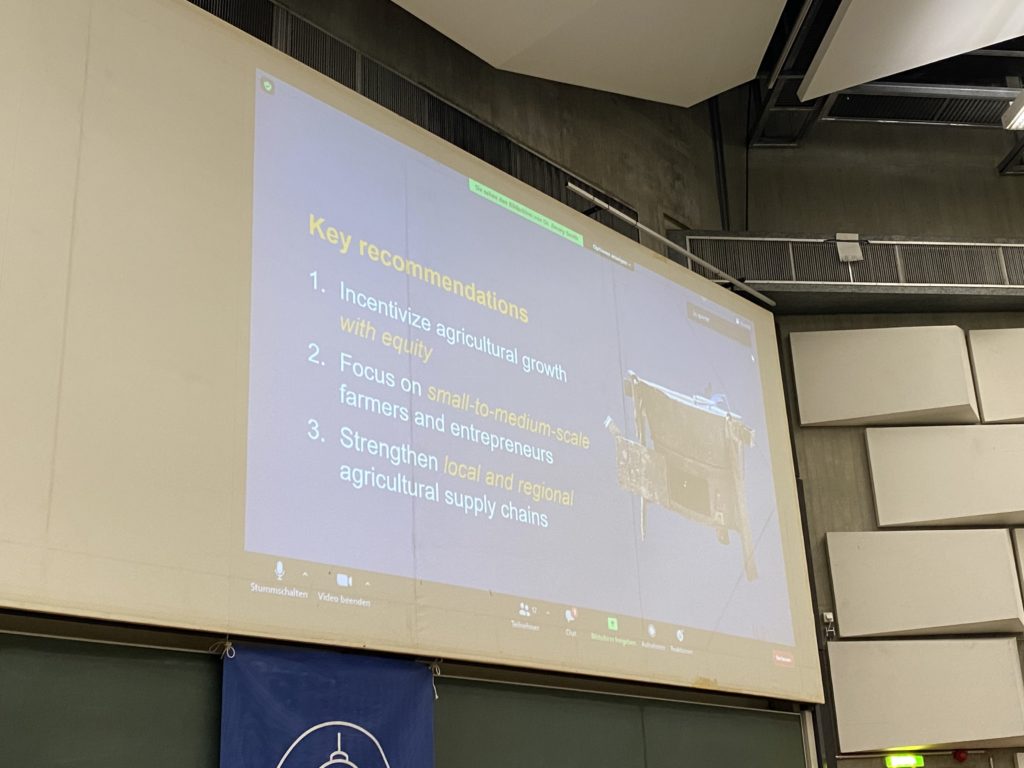

Sustainability to Dr. Smith is of 2 dimensions: Economic, which means an increase in incomes for smallholder farmers, who need to escape from poverty. Again, we are faced with the irony of those who engage in farming being the most hungry & poor among us. Social sustainability is the other dimension which means the inclusion of women and youth. There is no one size fits all solution – says Dr. Smith, and one uniform planetary diet will not meet our needs. Rather, the 3 shifts we need to transform food agriculture and feed people in the developing world are:

- Increasing investment, to respond to the number of people who depend on agriculture. This number ranges from 20-60% of the population, depending on which country you check. Agriculture also accounts for 25-50% share in some economies.

- Focus on small – medium scale farmers, entrepreneurs, not as a romantic gesture but simply because they produce most of the world’s food.

- Strengthen local & regional supply chains. A shift, suggests Dr. Smith is needed away from export focus to establishing stronger local chains instead. By doing this we can lower environmental footprints and reduce costs for farmers.

Birds, Bats & Macadamia Nuts

Next comes Prof Ingo Grass with an ecological perspective. We are all part of nature, however, and, because of that, we are also changing nature. Land use, he asserts, is by far the most prominent driver of biodiversity change and the ecosystems we have today are about 50% less of what we used to have a few decades ago. Mostly due to agriculture, 75% of species may face extinction in the coming decades. This is why Prof. Grass warns that modern industrial agriculture will come to an end – simply because it is based on using finite resources e.g oil, gas and water but also soils. Intensive meat production for example is an inefficient way to make use of plant biomass.

His suggestions to do things better include ecological intensification and diversified farming systems. Moreover, the greatest benefit we can receive from these practices is when we combine them. One good example of ecological intensification is good old macadamia nuts, an emerging top export crop for South Africa. The growth of macadamia highly relies on ecology, certain bee species are required for pollination, and then biological agents are needed for pest control which is often an issue with mono cultures. At first, farmers in South Africa used commercial pesticides for macadamia plantations on a large scale – spraying them from helicopters or drones. However, studies by Prof. Grass & his team found that most of the insects being killed were not the intended target. However, the macadamia pests are natural prey to certain species of birds and bats. The research team carried out exclusion studies by completely blocking out experimental macadamia fields from access to birds and bats and comparing this to the exposed fields without pesticide use. As soon as the birds & bats were excluded, there was a dramatic loss in crop yields. This shows that the creatures were capable of acting as biological pest control for the macadamia crops. These results were shown to the farmers – birds and bats could help prevent pests without need for expensive pesticides. For smallholder farmers, this was also an incentive to diversify their farm lands and keep some forest land which is a natural habitat for these creatures, in order to increase their numbers.

For diversified farming systems, Prof. Grass cited the example of Silvopastures, which is the integration of trees and grazing livestock operations on the same land. According to Prof Grass, they are more productive than traditional livestock systems by producing healthier soils and animals, with more economic viability.

He leaves us with the questions: Why aren’t examples like these happening more often? The answer: It takes a lot of investments and knowledge to convert from traditional systems to initiatives like this.

“Whatever we do is always embedded in a political and social arena.” says the Professor “and requires thinking in the socio ecological perspective… from the farmers to the political systems.”