Pastoralist Lessons in Coexistence and Climate Adaptation.

As climate change renders weather patterns increasingly unpredictable, pastoralists seize this variability as an opportunity. Their freedom of movement enables sustainable use of the environment to produce food. In contrast, systems that depend on predictability require constant control and consume vast natural resources. This option was never truly sustainable, and with global climate change is meeting its limits. Pastoralists, instead, turn environmental variability into food and are walking the path to sustainable food production systems.

At Tropentag 2025, the ‘Perspectives on Pastoralism Film Festival’ presents an awe-inspiring range of short films on pastoralist across the Earth. We meet a diversity of characters, like the Greek shepherd philosopher Vasilis, Maasai tribespeople and award-winning indigenous climate activist Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim.

The film festival starts with lessons in gentleness and attentiveness from Hungarian herder László Sáfián. He only sparingly uses his herding dog to drive the sheep, but prefers to calmly rouse the two leading rams with his voice. Knowing each sheep by name, he says, “every sheep has its own place in the flock.” Sitting among his sheep, he reflects emotionally, “there are still inexplicable noises that strike me to this day -the crisp sound of the sheep tearing at the grass and the sound of the bells, like a symphony.” His intuitive method allows the flock to graze evenly. From within, the sheep’s movements may seem chaotic, but drone footage reveals a flowing and harmonious rhythm.

Moving on to the Greek mountains, we meet young shepherd-philosopher Vasilis Fourkiotis. Sent to university by his family of shepherds, he ultimately returned to the mountains after realizing, ‘by what I am doing here, I am contributing more to nature.’ By walking the mountains, he feels able to embody academic concepts like deep ecology and indigenous ways.

‘Shepherding requires anarchy.’ Vasilis Fourkiotis.

Against an ordered world of control and monocultures, he defends the human spirit ‘My soul lives inside these grasslands, spirits inhabit this nature’. Even the wolf, often seen as the natural enemy of the shepherd, is embraced in his worldview.

‘When I see the wolf, I feel like I see myself’ Vasilis Fourkiotis exclaims.

‘Vasilis loves his sheep and slaughters them.’ Vasilis says as he argues for embracing this parallel reality, against the dualism of our times, where everything is either one or the other.

As a modern day shepherd, he is struggling with the current market, where dealers pay 0.4 cent to sell for 6 euros. ‘you’d rather give it to the dogs then to the dealer’ says his father, Vasilis concurs: ‘you are not your own boss’.

His grandfather has shaped the paths they now thread in the mountains, and he feels at one with his ancestors in the wilderness. Still, he worries that the mountains will soon remain alone.

In Spain’s Picos de Europa, the conflict between wolves and shepherds remains a daily reality. The Iberian wolf once came close to extinction, and to this day many wolves are still poisoned or otherwise killed by humans.

‘Red riding hood told me that the wolf was bad.’ Asturian shepherd.

He recently changed his perspective though, as he welcomed Mastiff herding dogs into his flock, who effectively protect the cows from wolves. Now he also sees the ecological value of the wolves, as they control sickness in wild animals by keeping numbers down, indirectly protecting his cows.

‘Wolves and shepherds, wasn’t it always like that?’ Young Asturian shepherd.

His words offer hope that coexistence is indeed possible.

The film festival next takes us to Maasai pastoralist who have received training by film makers to shoot their own documentary. The Maasai share a keen understanding of long-term causalities in nature, ”you should not cut the green trees, because there will be no rains”. Their wisdom, connecting forests to rainfall, anticipates scientific findings only recently confirmed.

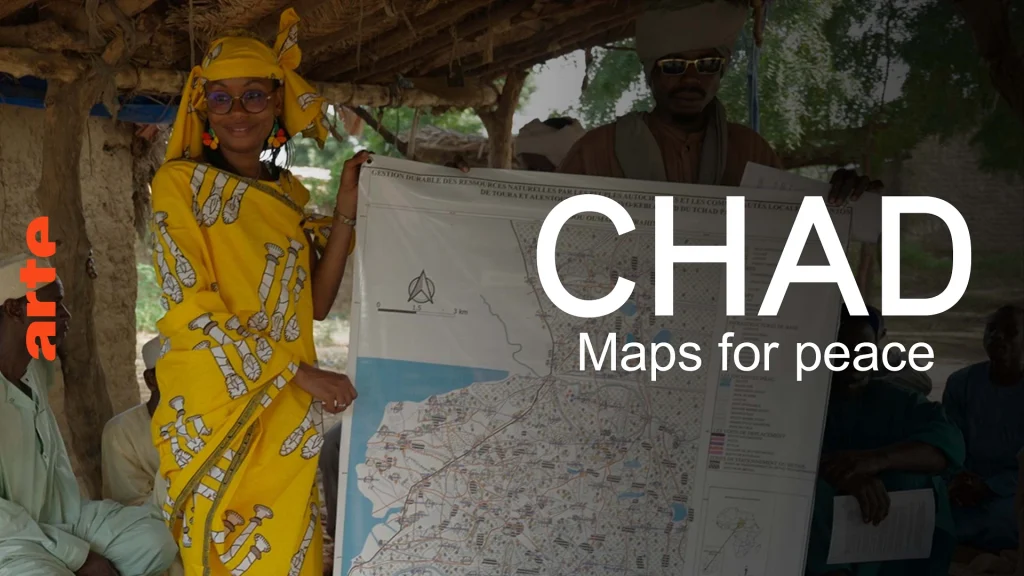

Our journey ends in Chad, where desertification advances at a devastating rate of 4 km per year, sparking violent outbreaks -particularly between pastoralist and farmers- over fertile lands, causing more than 500 deaths in the past year alone. Award winning activist Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim started reconciliation work using participatory mapping or indigenous mapping, where she works with locals to create intricate maps of their surroundings and resources. These maps open dialogue, ensuring pastoral corridors remain free of crops, to prevent conflict between grazing animals and farms.

“Indigenous people protect 80% of global biodiversity,” Ibrahim stresses, “therefore we must put indigenous people at the heart of climate solutions. With her participatory mapping project, she is protecting indigenous shepherds as well as farmers, to keep living in harmony with the land, and with each other.

Through this awe-inspiring film festival, we can walk with the shepherds of the world, if only briefly, to come to understand the profound wisdom they have gained through their immersion in and attentiveness to the natural world. Hopefully we come away inspired to do what we can to protect this wondrous earth and all that bravely walk its winding paths.

The ”Perspectives on Pastoralism Film Festival” is a valuable contribution to the UN designated International Year for Rangelands and Pastoralists 2026. Did you know that you can organize your own screenings on pastoralism? The films are freely available upon request. Discover more films and keep learning: https://www.pastoralistfilmfestival.com/

Many thanks to Anthony Denayer, co-director of the Perspectives on Pastoralism Film Festival, for introducing the films, facilitating dialogue at Tropentag 2025, and supporting the creation of these articles.

Film titles and makers:

| Film title | Filmmakers |

| Pastoralism is the future | CELEP |

| An afternoon on the pasture | Zsolt Molnár & Sándor Karácsony |

| Indigenius Loci | Vicky Markolefa |

| Sharing the Land | Ofelia de Pablo & Javier Zurita |

| The Dangar Strife – An Age-Old Ecosystem under Duress | Siddharth Kulkarni |

| Maasai Voices on Climate Change | Nickson ole Kirrokorr et al. |

| Maps for Peace | Sébastien Mesquida |